When people ask what it’s like where I live, I tell them it’s paradise. If they look skeptical, I explain that within a ten minute drive I can dig clams, buy fireworks, visit four different breweries, get a tattoo, and buy raw milk from a shed next to the stalls housing the cows who made it. Of course, that makes for a long day.

The thing about milk is, it’s perfect. You can, and did, live on it for months. I’m well aware that many adults around the world can’t digest animal dairy products too well, but if you can, count yourself lucky and read on. I actually had the opposite problem. I was allergic to cow’s milk as a baby, and failed to thrive until they stuck me on a bean-based formula named Mull-soy, after its inventor, a Mr. Muller. I eventually grew to love dairy products and became rather indifferent to soybeans. This might be what psychiatrists call transference.

But on to ricotta, the trembling soul of newborn cheese. I learned to make ricotta in self defense. Cheesemaking always seemed too much like chemistry to me, so I was happy to buy it from my friend Luca Mignona at his caseificio the next town over. But Luca eventually had to close his retail outlet, and while I could soldier on without his superb if pricey mozzarella – the world is full of acceptable mozzarella – the ricotta he made in the traditional manner, from leftover mozzarella whey (ricotta means recooked), was a singularity. Especially as it came from the cows down the street.

If you were to see this leftover whey, which is thin and greenish, you wouldn’t think it had enough gumption left to become real cheese, but it works. Mozzarella making uses the enzyme rennet and relatively low heat and acid, which cracks off mainly the casein proteins in the milk. The whey proteins form the remaining twenty percent, and are separated out by reheating the whey to a higher temp, and adding, if needed, a bit more acid (or just letting things sit and ferment for a couple of days, which accomplishes the same goal).

It’s not wrong to think that mozzarella, with its first dibs on the milk, comes out ahead. Casein liquifies at body temperature, giving cheese its melty lusciousness. But the whey proteins are stalwart and sensitive, and project the grassy freshness of the original product. Luca’s fresh ricotta tasted nothing at all like anything else I could buy.

With Luca and his vats of whey now missing from my life, a bunch of experiments ensued. The internet, as usual, seemed full of recipes created by Russian bots intent on sowing discontent with western cuisine. Most yielded cheese with the nursery aroma of overcooked milk, along with off-flavors of vinegar or lemon juice. No no no.

Eaters, as I explained above, I have access to terrific milk. With stuff like this, you want to screw with it as little as possible. Buy some citric acid from a nice cheese-making supply house (or some middle eastern markets). Use just enough to crack off the proteins. And be really careful about heat.

I know you may not have access to raw, fresh milk. It’s still worth a try. I’ve also read, in numerous places, to avoid milk that says it is ultra-pasteurized. This sounds like good advice, though I have personally made great creme fraiche from ultra-pasteurized heavy cream, which wasn’t supposed to work. It’s a big, crazy world out there.

One thing I have to say is that my homemade ricotta, though glorious, is not the same as Luca’s. His whey-based ricotta was less fatty, and more delicate. But I’m liking my own in recipes where the extra richness works. It can stand in for whipped cream next to a tart dessert. It wants to turn dishes inside out, becoming the star ingredient in a deconstructed spanakopita, or an exploded pumpkin ravioli.

But you can also keep it extra simple. On a weeknight, just grate in a generous fingertip of nutmeg and then soothe it over any pasta shape, adding a few tablespoons of the cooking water and some leftover vegetables. It’s like having your own private stairway to heaven.

Recipe: Fresh raw milk ricotta

A semi-pro fresh ricotta cheese made with raw milk.

-Full Post-

You'll need a good, thick saucepan, a skimmer with a mesh screen or small holes, a strainer or official ricotta basket, and a fast-acting thermometer. Start by dissolving the citric acid crystals in the warm water. With luck, you won't need more than half of the liquid. We'll see.

Start warming the milk over medium-high heat, stirring frequently enough to keep it from coating the bottom of the pan. Test the temperature frequently, turning the heat down to medium as you approach 165 degrees F.

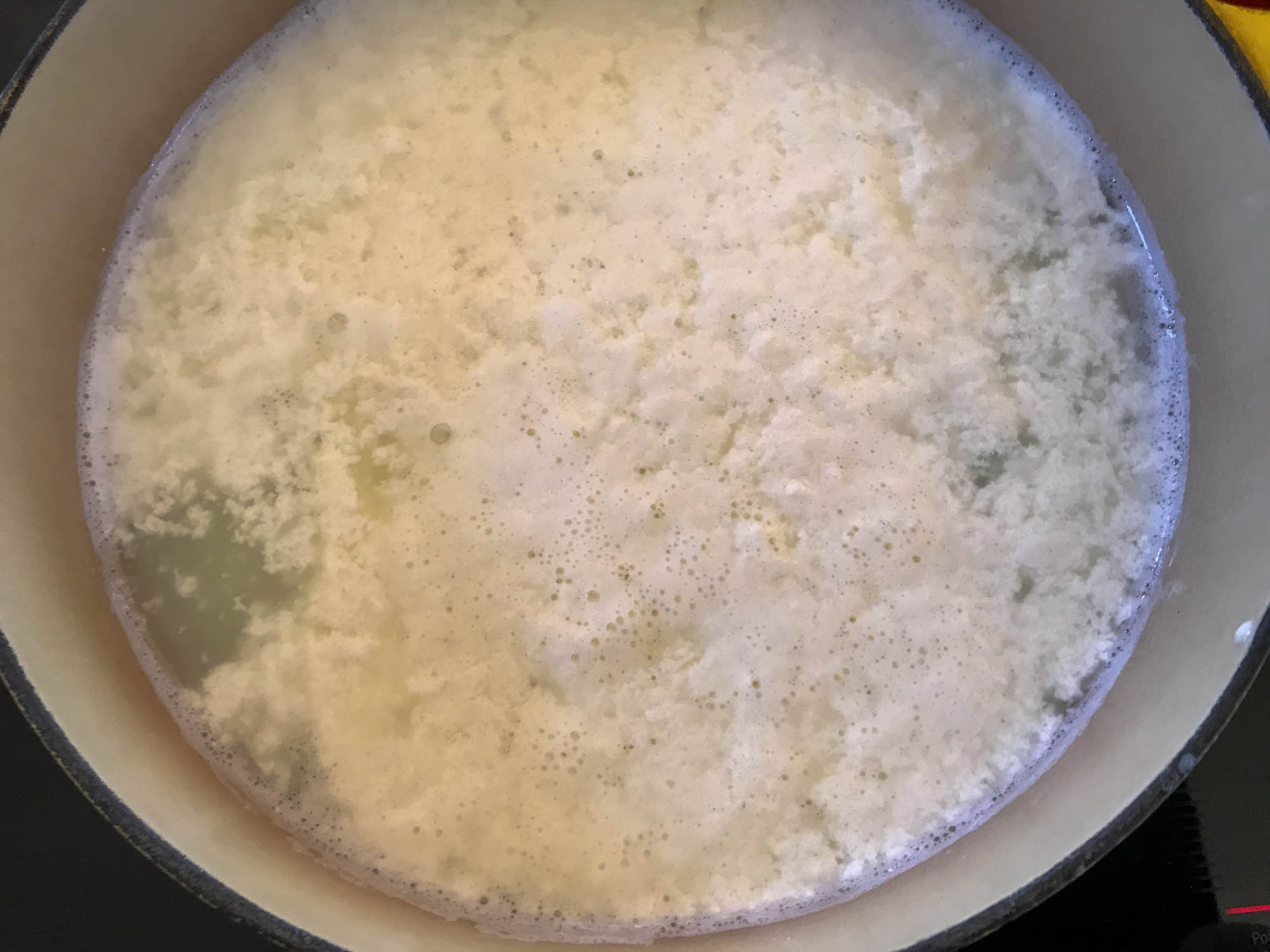

When the milk hits 165, add just 1 tablespoon of the acid solution. From this point forward, keep stirring to a minimum - just float the spoon around gently. You're looking for the proteins to curdle up into a watery mass, clearly separate from the watery, greenish whey. If this doesn't happen within a minute or two, add another tablespoon of the acidulated water.

If there's still no joy and your milk is between 165 and 170, you can try a bit more heat and a bit more acid. But I'm betting two tablespoons (that is, one teaspoon of dissolved citric acid) will be enough. Let's imagine it is.

Continue letting the heat build up, monitoring it carefully and not letting it get beyond 195 degrees F - remove from the heat completely a few degrees before that. The ricotta will improve, and you'll get a better yield, with a five minute rest between 185 and 195. Stir only gently and occasionally, to let the curds huddle up and float - you only want to keep them from sticking to the sides or the very bottom of the pan.

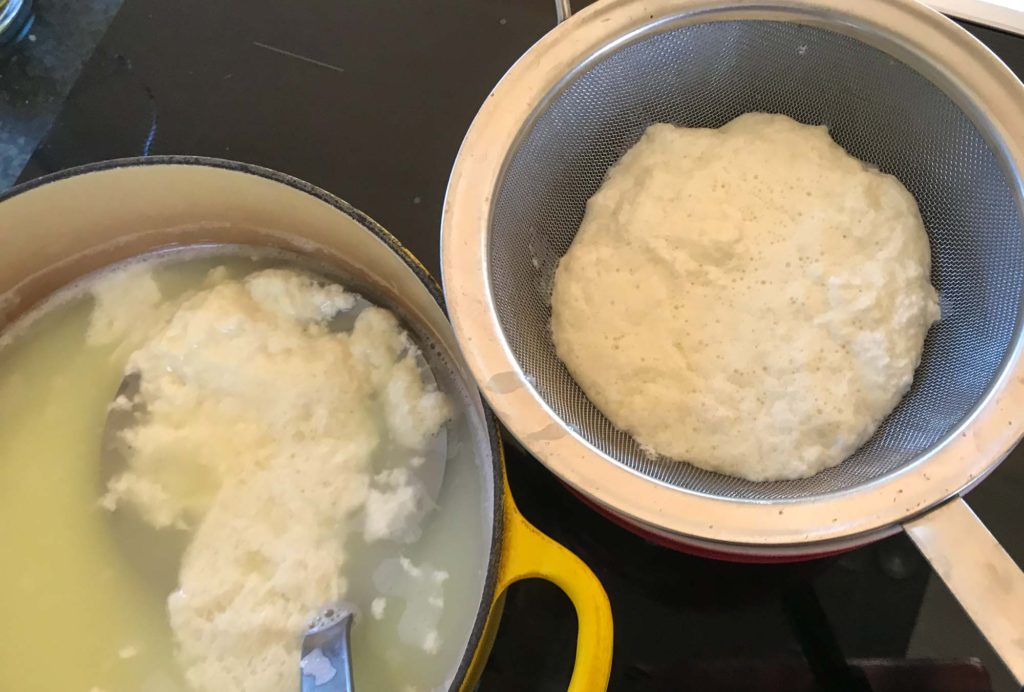

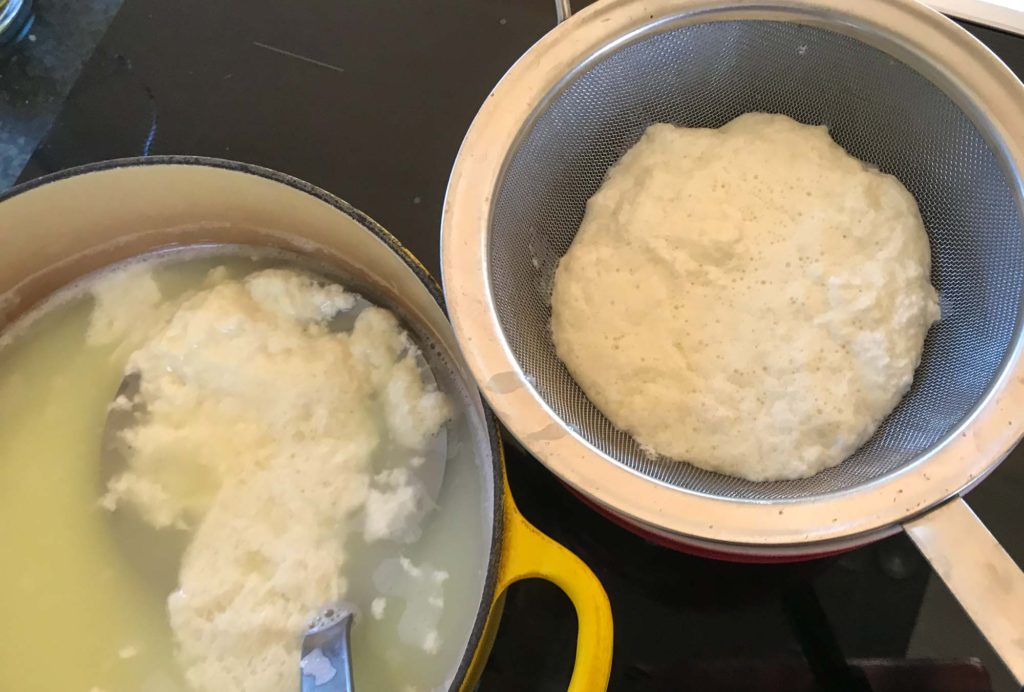

After their relaxing bath, skim the curds off into a strainer set over a small bowl. The longer it sits and drains, the drier the end product - 10 minutes is about right for most uses. Stir it up, adding just a pinch of salt if you like, and refrigerate. Keeps well for about five days.

Such a simple thing, and yet so variable. Your yield will be around a cup of lovely ricotta for a half-gallon of milk, but it will weigh around 10 or 12 ounces, and go a long way. You are advised to avoid ultra-pasteurized milk (warning - many organic brands are ultra pasteurized), as this flash-heating process affects the protein structure and they may not want to separate at all.

If you find a milk that works well, stick with it. My very good friends at New England Cheesemaking Supply can help you with citric acid, official ricotta baskets, additional recipes and excellent advice. Given a zip code, they can even tell you where to get good milk in your area.

It's tough not to eat this ricotta straight up for breakfast with some fresh fruit, but try my recipes for nestling it next to a pie, making naked spanakopita, or turning pumpkin ravioli inside out.

Ingredients

Directions

You'll need a good, thick saucepan, a skimmer with a mesh screen or small holes, a strainer or official ricotta basket, and a fast-acting thermometer. Start by dissolving the citric acid crystals in the warm water. With luck, you won't need more than half of the liquid. We'll see.

Start warming the milk over medium-high heat, stirring frequently enough to keep it from coating the bottom of the pan. Test the temperature frequently, turning the heat down to medium as you approach 165 degrees F.

When the milk hits 165, add just 1 tablespoon of the acid solution. From this point forward, keep stirring to a minimum - just float the spoon around gently. You're looking for the proteins to curdle up into a watery mass, clearly separate from the watery, greenish whey. If this doesn't happen within a minute or two, add another tablespoon of the acidulated water.

If there's still no joy and your milk is between 165 and 170, you can try a bit more heat and a bit more acid. But I'm betting two tablespoons (that is, one teaspoon of dissolved citric acid) will be enough. Let's imagine it is.

Continue letting the heat build up, monitoring it carefully and not letting it get beyond 195 degrees F - remove from the heat completely a few degrees before that. The ricotta will improve, and you'll get a better yield, with a five minute rest between 185 and 195. Stir only gently and occasionally, to let the curds huddle up and float - you only want to keep them from sticking to the sides or the very bottom of the pan.

After their relaxing bath, skim the curds off into a strainer set over a small bowl. The longer it sits and drains, the drier the end product - 10 minutes is about right for most uses. Stir it up, adding just a pinch of salt if you like, and refrigerate. Keeps well for about five days.

Such a simple thing, and yet so variable. Your yield will be around a cup of lovely ricotta for a half-gallon of milk, but it will weigh around 10 or 12 ounces, and go a long way. You are advised to avoid ultra-pasteurized milk (warning - many organic brands are ultra pasteurized), as this flash-heating process affects the protein structure and they may not want to separate at all.

If you find a milk that works well, stick with it. My very good friends at New England Cheesemaking Supply can help you with citric acid, official ricotta baskets, additional recipes and excellent advice. Given a zip code, they can even tell you where to get good milk in your area.

It's tough not to eat this ricotta straight up for breakfast with some fresh fruit, but try my recipes for nestling it next to a pie, making naked spanakopita, or turning pumpkin ravioli inside out.

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.